Oops, I almost forgot!

The current Historical Sew Fortnightly challenge is Robes and Robings. After completing four challenges on the trot, I'm taking a bit of a break, but you can see all the fabulous things other Challengers have made here and here.

Friday, 30 August 2013

Sunday, 25 August 2013

1930s sewing books

I’ve not been able to do much sewing this week, so for today’s post I thought I’d show some of the old needlework books I’ve collected over the years. They have all come from charity shops for a few pounds, but in the last few years the supply has dried up; possibly other people have started to realise just how useful they are!

None of the three books have a publication date, but from the illustrations it’s clear that they all come from the 1930s.

Although the 1930s are usually associated with the Depression, for many middle class families with a regular income they were a comfortable time with a clear rise in living standards. In particular, with more and more homes having an electricity supply, labour-saving appliances became “must have” items.

The extra leisure time which vacuum cleaners, washing machines and the like provided led to an increased interest in pursuits such as crafts (especially making things for your new, modern home), and a number of publications appeared to cater for this interest.

First up is “The Art of Needlecaft” by R. K and M.I.R. Polkinghorne. I’ve not been able to find out much about the splendidly-named authors, but they wrote on a wide range of subjects other than needlecraft; bible stories, teaching aids and famous men and women, to name a few. The book’s cover lists the subjects covered in its 600-plus pages; dressmaking,embroidery, curtains, tapestry, knitting and crochet, rug making, weaving, basketry, raffia work, leather work, stencilling, batiks and new ideas. Phew!

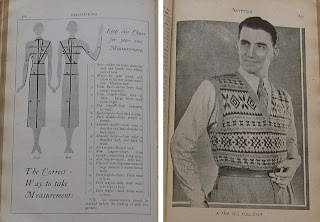

There are plenty of diagrams (328 according to the frontispiece, as well as 32 “art plates”), some simple, and some more complex.

The diagrams of how to do things such as embroidery stitches are timeless, the illustrations of how to use them rather less so.

The chapter on “Indian or Coiled Basketry” prompted me to take another look at a small basket which my Granny R made, I think in the 1920s, and which I still use to hold bits and bobs.

In fact there are even more subjects covered than listed on the cover. Presumably “Plain Sewing” and “Patching and Mending” were not considered exciting enough to be listed.

The “Dressmaking” chapter assumes that the reader is working from a commercial pattern, but still includes useful information such as how to make a belt. Handy if you are making up Maudella 5151.

There is a lot of information in this book which is still useful, although I think I’ll pass on the advice about knitting “one’s own underwear”!

Next up is “Weldon’s Encyclopedia of Needlework”. Yes that Weldon’s, the people who brought you this...

And this...

This is an even bigger book; well over 800 pages, and almost 2,000 illustrations, split into six books. According to the foreword;

“You will not find the latest fads and passing fashions of a mere season in these pages. On the contrary, this Encyclopedia has been so complied that it will not date, and it will be found just as useful in years to come as it is to-day.”

Book one is ”Embroidery”, which takes up almost half of the book. While I’m not entirely convinced about the ‘not dating’ part of the foreword (see evidence above), this section does give plenty of examples of how embroidery techniques have been used in the past, with a lot of photographs of old pieces, mostly from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The occasional modern piece does appear, such as this lovely example of how net embroidery could be used in a contemporary style.

The final book is the “Good Needlework Gift Book”, or as it is called inside, “Good Needlework Second Gift Book”.

“Good Needlework” was a monthly magazine, so I’m guessing that the Gift Books were almost like a Christmas annual. Clearly they were sold more widely than just in Britain, as the book “may only be exported to Australia, New Zealand or South Africa through the appointed agent”, and details were given of how overseas readers could obtain the transfers used for many of the designs.

Whereas the other two books have plain covers (although they may originally have had dust jackets), this book has a coloured cover and frontispiece, possibly to enhance its use as a gift.

It even has some coloured pages inside, albeit only a couple of pages at a time, and in two colours.

Most of the items in the gift book require the use of transfers, although the illustrations are so clear that you could recreate the design from them if you wanted to. There are also some cross stitch designs, with the chart printed in the book.

I particularly like these boxes, made by covering empty powder boxes with embroidered coloured linen.

There are a few projects which do not require either a chart or a transfer, such as these organdie chrysanthemums to trim an evening dress.

There is a whole section on “Lingerie Embroidery”. The word “dainty” features heavily here – a far cry from knitting your own underwear!

I just love the illustrations of this book, they are so redolent of the 1930s.

It’s not all lingerie and powder boxes however; there are lots of things for the home here as well, such as tea cosies, tablecloths and napkins, cushion covers, chairbacks, and even a cover for the Radio Times.

Looking at this book now, I could imagine having a go at making not just some of the items in it, but some of the dresses in the illustrations as well!

I’ll finish with these two ladies, enjoying their new-found leisure time.

None of the three books have a publication date, but from the illustrations it’s clear that they all come from the 1930s.

Although the 1930s are usually associated with the Depression, for many middle class families with a regular income they were a comfortable time with a clear rise in living standards. In particular, with more and more homes having an electricity supply, labour-saving appliances became “must have” items.

|

| The perfect Christmas gift? |

The extra leisure time which vacuum cleaners, washing machines and the like provided led to an increased interest in pursuits such as crafts (especially making things for your new, modern home), and a number of publications appeared to cater for this interest.

First up is “The Art of Needlecaft” by R. K and M.I.R. Polkinghorne. I’ve not been able to find out much about the splendidly-named authors, but they wrote on a wide range of subjects other than needlecraft; bible stories, teaching aids and famous men and women, to name a few. The book’s cover lists the subjects covered in its 600-plus pages; dressmaking,embroidery, curtains, tapestry, knitting and crochet, rug making, weaving, basketry, raffia work, leather work, stencilling, batiks and new ideas. Phew!

There are plenty of diagrams (328 according to the frontispiece, as well as 32 “art plates”), some simple, and some more complex.

The diagrams of how to do things such as embroidery stitches are timeless, the illustrations of how to use them rather less so.

|

| Very 1930s designs . . . |

|

| . . . and very 1930s hair |

The chapter on “Indian or Coiled Basketry” prompted me to take another look at a small basket which my Granny R made, I think in the 1920s, and which I still use to hold bits and bobs.

|

| Granny R's handiwork |

In fact there are even more subjects covered than listed on the cover. Presumably “Plain Sewing” and “Patching and Mending” were not considered exciting enough to be listed.

The “Dressmaking” chapter assumes that the reader is working from a commercial pattern, but still includes useful information such as how to make a belt. Handy if you are making up Maudella 5151.

There is a lot of information in this book which is still useful, although I think I’ll pass on the advice about knitting “one’s own underwear”!

Next up is “Weldon’s Encyclopedia of Needlework”. Yes that Weldon’s, the people who brought you this...

|

| Yes I've shown this before, but it always makes me smile |

And this...

|

| Even more 'to the point' titles |

This is an even bigger book; well over 800 pages, and almost 2,000 illustrations, split into six books. According to the foreword;

“You will not find the latest fads and passing fashions of a mere season in these pages. On the contrary, this Encyclopedia has been so complied that it will not date, and it will be found just as useful in years to come as it is to-day.”

|

| A typical elongated 1930s figure in the diagram, and a tucked-in jumper |

Book one is ”Embroidery”, which takes up almost half of the book. While I’m not entirely convinced about the ‘not dating’ part of the foreword (see evidence above), this section does give plenty of examples of how embroidery techniques have been used in the past, with a lot of photographs of old pieces, mostly from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

|

| Indian embroidery example |

The occasional modern piece does appear, such as this lovely example of how net embroidery could be used in a contemporary style.

|

| Very 'moderne' |

The final book is the “Good Needlework Gift Book”, or as it is called inside, “Good Needlework Second Gift Book”.

“Good Needlework” was a monthly magazine, so I’m guessing that the Gift Books were almost like a Christmas annual. Clearly they were sold more widely than just in Britain, as the book “may only be exported to Australia, New Zealand or South Africa through the appointed agent”, and details were given of how overseas readers could obtain the transfers used for many of the designs.

Whereas the other two books have plain covers (although they may originally have had dust jackets), this book has a coloured cover and frontispiece, possibly to enhance its use as a gift.

|

| Colour! |

It even has some coloured pages inside, albeit only a couple of pages at a time, and in two colours.

|

| Pages 53 and 56 are also in colour (well, green and pink) |

Most of the items in the gift book require the use of transfers, although the illustrations are so clear that you could recreate the design from them if you wanted to. There are also some cross stitch designs, with the chart printed in the book.

I particularly like these boxes, made by covering empty powder boxes with embroidered coloured linen.

There are a few projects which do not require either a chart or a transfer, such as these organdie chrysanthemums to trim an evening dress.

|

| Pretty. But possibly, slightly tickly? |

There is a whole section on “Lingerie Embroidery”. The word “dainty” features heavily here – a far cry from knitting your own underwear!

I just love the illustrations of this book, they are so redolent of the 1930s.

|

| The perfect period dressing table |

It’s not all lingerie and powder boxes however; there are lots of things for the home here as well, such as tea cosies, tablecloths and napkins, cushion covers, chairbacks, and even a cover for the Radio Times.

Looking at this book now, I could imagine having a go at making not just some of the items in it, but some of the dresses in the illustrations as well!

|

| Sleeves and a cape! |

I’ll finish with these two ladies, enjoying their new-found leisure time.

Sunday, 18 August 2013

Blue Velvet

I've been away this weekend, on a residential Middle Eastern dance course with friends. As with most of these events, there was a party on the Saturday night, so of course I needed a new dress.

This was the perfect excuse to make something from a fabulous blue and gold devoré velvet which I bought last year from the fabric department of Bombay Stores in Bradford. Well worth a visit if you are ever in the area, but be prepared to be there for some time; there are lots of lovely things to drool over.

The burnt-out areas on this fabric are quite large, which makes it fairly see-through. Apologies for the very blurred photograph, but it does give an idea of just how sheer the material is.

The dress would definitely need a lining, but what colour would be best? Dark or light?

To find out, I draped one side of my dress form with a dark blue silky fabric from my stash. I didn't have any suitable yellow/gold fabric, so I improvised with some cream coloured lining with yellow chiffon over it.

Then I draped the fabric over the top.

From a distance, there wasn't much difference. Close up, the lighter side showed up the blue velvet swirls more clearly, but the gold threads running through the backing fabric were lost. They showed up more clearly over the darker side.

I decided I preferred the effect of the dark lining. (This also had the advantage of using up more stash fabric!)

The main part of the dress is just a simple shift shape, with side slits, bust darts and some shaping in the side seams. I made this part up first in the lining fabric, which also acted as a test piece for making the dress itself. The sleeves were drafted with a flatter than usual sleeve head to allow more arm movement: something I often do for Middle Eastern dance clothes, especially if they are made from non-stretch fabric. I also moved the sleeve seam from underarm to the front, to allow the lower part of the sleeve to fall free in a similar style to this illustration.

I didn't have enough fabric to match the front and back pieces at the side seams, but I did manage to cut the pieces out so that the pattern is symmetrical. Then I made up the dress the same way as the the lining, and set the sleeves in. The lining was then attached to the dress around the neck and along the side slits.

As I mentioned in my previous post, I only started drafting the pattern for the dress on Monday evening, and late Monday evening at that. As a result, by the time we set off on Friday morning there was still some work to do.

The course was held at Haileybury School in Hertfordshire, and much of the hand sewing to finish the dress was done in the commonroom in the breaks between workshops (where the photograph below was taken). I even found time to make a matching hairband from a remnant to complete the outfit.

This was the perfect excuse to make something from a fabulous blue and gold devoré velvet which I bought last year from the fabric department of Bombay Stores in Bradford. Well worth a visit if you are ever in the area, but be prepared to be there for some time; there are lots of lovely things to drool over.

The burnt-out areas on this fabric are quite large, which makes it fairly see-through. Apologies for the very blurred photograph, but it does give an idea of just how sheer the material is.

|

| Wall, curtain and window clearly visible through the fabric |

The dress would definitely need a lining, but what colour would be best? Dark or light?

To find out, I draped one side of my dress form with a dark blue silky fabric from my stash. I didn't have any suitable yellow/gold fabric, so I improvised with some cream coloured lining with yellow chiffon over it.

|

| Ready for testing |

Then I draped the fabric over the top.

From a distance, there wasn't much difference. Close up, the lighter side showed up the blue velvet swirls more clearly, but the gold threads running through the backing fabric were lost. They showed up more clearly over the darker side.

I decided I preferred the effect of the dark lining. (This also had the advantage of using up more stash fabric!)

The main part of the dress is just a simple shift shape, with side slits, bust darts and some shaping in the side seams. I made this part up first in the lining fabric, which also acted as a test piece for making the dress itself. The sleeves were drafted with a flatter than usual sleeve head to allow more arm movement: something I often do for Middle Eastern dance clothes, especially if they are made from non-stretch fabric. I also moved the sleeve seam from underarm to the front, to allow the lower part of the sleeve to fall free in a similar style to this illustration.

|

| Ghawazee dancers, David Roberts, 1842 |

I didn't have enough fabric to match the front and back pieces at the side seams, but I did manage to cut the pieces out so that the pattern is symmetrical. Then I made up the dress the same way as the the lining, and set the sleeves in. The lining was then attached to the dress around the neck and along the side slits.

As I mentioned in my previous post, I only started drafting the pattern for the dress on Monday evening, and late Monday evening at that. As a result, by the time we set off on Friday morning there was still some work to do.

The course was held at Haileybury School in Hertfordshire, and much of the hand sewing to finish the dress was done in the commonroom in the breaks between workshops (where the photograph below was taken). I even found time to make a matching hairband from a remnant to complete the outfit.

|

| The finished dress |

Sunday, 11 August 2013

Separates

The current Historical Sew Fortnightly challenge is Separates.

I wasn’t going to take part in this challenge, I really, really wasn’t. I’m partway through Vogue 2787, and want to test out my pattern alterations. I have an ever-growing backlog of other sewing to do, some of it with seriously alarming deadlines (this Friday, a dress, for which I haven’t even drafted the pattern yet – aargh!). Plus, as I am so new to historical costuming, I don’t have any ‘orphan’ items which need another garment to make them into a complete costume.

Then, when I was looking for something in my overflow workbox (you mean you don’t have one?) I found this, carefully folded in a cotton handkerchief.

I made this a long time ago, more than a decade ago in fact. It is Torchon lace, and it was made to size to trim a Folkwear Armistice Blouse. However I never got round to making the blouse, and in time forgot about the lace altogether.

Of course, having found it I didn’t have the heart to just wrap it back up and put it away again. And the Separates challenge was coming up. . . . .

Although the lace looks white, it is actually very slightly off-white. This meant that placed over the various very white cottons in my stash, it just looked a bit grubby. A deeper delve into Stash-land unearthed a fine lawn which was both the right colour and perfect for the period.

I have made the blouse before, but so long ago that I don’t remember how well or otherwise it came together. Fortunately I did remember that The Dreamstress had made the same blouse last year, so I re-read her posts. I can confirm that a) the sleeves are indeed far too long, even for my long arms, and b) the instructions leave a lot to be desired. In the end I just ignored them and relied on my own methods, with help from my trusty copy of Vogue Sewing for the sleeve plackets.

I’m not quite sure what dimensions I thought I was working to when I made the lace. The piece for the collar fits perfectly, the pieces for the front panel less so.

Even allowing for the fact that with bobbin lace you can’t just start and finish where you like, these are far too long.

This has been a very rushed project, and in some places it shows. I forgot to make the necessary alterations for my short torso when I cut the pieces out; so even with the lace at the top, the centre panel was alarmingly low. I had to move it up, which is why it is shorter than the rest of the blouse. I also had to reposition the gathered section and the tie at the back of the blouse. I followed The Dreamstress’s advice and used ribbon rather than make the tie from fabric. I also ditched the extra, fold-back element of the ciffs

The combination of very fine fabric and a dark dress form means that all the seams and facings really show up; these would be less obvious over period underwear. All the seams are French seams, which worked well. The buttonholes on the cuffs are hand-sewn, which worked considerably less well. Clearly I need a lot more practice.

Even before I discovered how bad my buttonhole technique is, I had decided that I didn’t want buttons down the front. I’d planned to use hooks and eyes instead, but the blouse is loose enough that it can be pulled on over the head. I just basted it together quickly for the photographs, which is why it’s a bit out of kilter.

To me the neckline seems very baggy; I might investigate some discrete gathering at the back under the collar to pull it in a bit. For all the faults however, at least the lace is now on a blouse as intended rather than folded up in a workbox.

The Small Print:

The Challenge: Separates

Fabric: Off-white cotton lawn from stash

Pattern: Folkwear Armistice Blouse

Year: 1918-ish (see below)

Notions: Hand-made Torchon lace, ribbon for tie, six buttons for cuffs

How historically accurate is it? To quote The Dreamstress's review of the pattern; “1980s does 1910s”

Hours to complete: About eight, of which about two were spent on the buttonholes (so much effort, to so little effect)

First worn: Not yet

Total cost: 90 pence for the buttons, 66 pence for ribbon, so £1.56 in total

I wasn’t going to take part in this challenge, I really, really wasn’t. I’m partway through Vogue 2787, and want to test out my pattern alterations. I have an ever-growing backlog of other sewing to do, some of it with seriously alarming deadlines (this Friday, a dress, for which I haven’t even drafted the pattern yet – aargh!). Plus, as I am so new to historical costuming, I don’t have any ‘orphan’ items which need another garment to make them into a complete costume.

Then, when I was looking for something in my overflow workbox (you mean you don’t have one?) I found this, carefully folded in a cotton handkerchief.

|

| Mystery items |

I made this a long time ago, more than a decade ago in fact. It is Torchon lace, and it was made to size to trim a Folkwear Armistice Blouse. However I never got round to making the blouse, and in time forgot about the lace altogether.

|

| The blouse pattern |

Of course, having found it I didn’t have the heart to just wrap it back up and put it away again. And the Separates challenge was coming up. . . . .

Although the lace looks white, it is actually very slightly off-white. This meant that placed over the various very white cottons in my stash, it just looked a bit grubby. A deeper delve into Stash-land unearthed a fine lawn which was both the right colour and perfect for the period.

I have made the blouse before, but so long ago that I don’t remember how well or otherwise it came together. Fortunately I did remember that The Dreamstress had made the same blouse last year, so I re-read her posts. I can confirm that a) the sleeves are indeed far too long, even for my long arms, and b) the instructions leave a lot to be desired. In the end I just ignored them and relied on my own methods, with help from my trusty copy of Vogue Sewing for the sleeve plackets.

I’m not quite sure what dimensions I thought I was working to when I made the lace. The piece for the collar fits perfectly, the pieces for the front panel less so.

|

| The collar edging - a perfect fit |

|

| The front panel, not so perfect |

Even allowing for the fact that with bobbin lace you can’t just start and finish where you like, these are far too long.

This has been a very rushed project, and in some places it shows. I forgot to make the necessary alterations for my short torso when I cut the pieces out; so even with the lace at the top, the centre panel was alarmingly low. I had to move it up, which is why it is shorter than the rest of the blouse. I also had to reposition the gathered section and the tie at the back of the blouse. I followed The Dreamstress’s advice and used ribbon rather than make the tie from fabric. I also ditched the extra, fold-back element of the ciffs

|

| The completed blouse |

The combination of very fine fabric and a dark dress form means that all the seams and facings really show up; these would be less obvious over period underwear. All the seams are French seams, which worked well. The buttonholes on the cuffs are hand-sewn, which worked considerably less well. Clearly I need a lot more practice.

|

| Buttonholes - could do better |

Even before I discovered how bad my buttonhole technique is, I had decided that I didn’t want buttons down the front. I’d planned to use hooks and eyes instead, but the blouse is loose enough that it can be pulled on over the head. I just basted it together quickly for the photographs, which is why it’s a bit out of kilter.

To me the neckline seems very baggy; I might investigate some discrete gathering at the back under the collar to pull it in a bit. For all the faults however, at least the lace is now on a blouse as intended rather than folded up in a workbox.

|

| A home for the lace at last |

The Small Print:

The Challenge: Separates

Fabric: Off-white cotton lawn from stash

Pattern: Folkwear Armistice Blouse

Year: 1918-ish (see below)

Notions: Hand-made Torchon lace, ribbon for tie, six buttons for cuffs

How historically accurate is it? To quote The Dreamstress's review of the pattern; “1980s does 1910s”

Hours to complete: About eight, of which about two were spent on the buttonholes (so much effort, to so little effect)

First worn: Not yet

Total cost: 90 pence for the buttons, 66 pence for ribbon, so £1.56 in total

Sunday, 4 August 2013

Vogue 2787 and Vogue 1004

I like to set myself a challenge from time to time, and I’ve certainly done that by deciding to tackle a pattern which has been on my 'to do' list for a while; Vogue 2787.

I’ve posted before about my need to alter patterns to get a good fit. As I have several Vogue patterns on my list, I decided to do the job properly, and identify exactly where I need to make alterations.

To do this I dug out another pattern I’ve had for a while; Vogue 1004. This is the Vogue fitting shell, or sloper. A fitting shell is a pattern for a plain, closely-fitted dress with a neckline that follows the base of the neck (also known as a jewel-neck), and a narrow skirt. McCall's and Butterick also make fitting shells, McCall's M2718 and Butterick B5746, although some online reviews suggest that the Vogue and Butterick patterns are identical. The pattern pieces of a fitting shell have much larger than usual seam allowances, so that there is plenty of scope for letting seams out if necessary. The idea is that once you have altered the fitting shell to fit you exactly, you can apply the same alterations to every pattern of that brand, and get a perfect fit every time.

The pattern instructions tell you to take detailed measurements first, and then use these to alter the pattern pieces before you start cutting out. They also recommend making the pattern up in woven (not printed) gingham, so that the grain of the fabric is clearly visible. However as I’ve made up Vogue patterns before, and they fitted reasonably well with a few alterations, I chose instead to cut the pattern pieces out without alterations, using my tried and trusted toile 'fabric' - frost fleece.

Frost fleece is available from garden centres or online. It is cheap; the 10 square metres pack above cost me less than £5.00. Unlike tissue paper, fleece does not tear easily, and pieces can be joined together using a sewing machine. Unlike fabric, it does not fray. I also like the fact that because it is translucent, you can clearly see the clothing underneath; so for example it is easy to tell where the waistline of a toile lies relative to your undergarments.

Finally, frost fleece is easy to draw on with pencil, felt tip or biro. When I designed my Eastern Influence dress I made a toile of the basic shape, then put it on the dress form and drew on the front neckline details. I then made the pattern by tracing off the pieces from the toile.

(Note: fleece is far less absorbent of ink than either fabric or paper, so while any marks made don’t rub off, a certain amount of ink transfers onto your fingers, your cutting table, and anything else the drawn-upon fleece brushes against.)

The area which I most wanted to check was the bodice length, so I marked the bust line onto the toile front pieces with red pen, and continued the line around the back. The fitting shell instructions are to make the dress up with a back opening, but I changed this to a front opening, to make it easier to get on and off.

When I tried the toile on it was easy to see that both the waist-to-bust and bust-to-shoulder sections were too long, and that I needed to shorten both. I had deliberately made the bodice up without sleeves, so that I could check if the armscye was too low. It wasn’t, so the bust-to-shoulder alteration needed to be made below the armscye.

This discovery makes altering Vogue 2787 to fit me, ahem, 'interesting'. The front of the dress has a reverse S-shaped curve up the centre, and long curved darts which extend almost from waist to bust. So, taking out 30mm between waist and bust, and a further 20mm between bust and armscye is going to be tricky.

On the pattern piece above, the large circles with a cross in them indicate the waist and bust lines. There's not a lot of room for manoeuvre.

There is no bust marking on the left front piece, so I will have to alter it in line with the right front.

Definitely challenging!

|

| V2787 - a modern reissue of a 1948 Vogue pattern |

I’ve posted before about my need to alter patterns to get a good fit. As I have several Vogue patterns on my list, I decided to do the job properly, and identify exactly where I need to make alterations.

To do this I dug out another pattern I’ve had for a while; Vogue 1004. This is the Vogue fitting shell, or sloper. A fitting shell is a pattern for a plain, closely-fitted dress with a neckline that follows the base of the neck (also known as a jewel-neck), and a narrow skirt. McCall's and Butterick also make fitting shells, McCall's M2718 and Butterick B5746, although some online reviews suggest that the Vogue and Butterick patterns are identical. The pattern pieces of a fitting shell have much larger than usual seam allowances, so that there is plenty of scope for letting seams out if necessary. The idea is that once you have altered the fitting shell to fit you exactly, you can apply the same alterations to every pattern of that brand, and get a perfect fit every time.

|

| Fitting shell in gingham |

The pattern instructions tell you to take detailed measurements first, and then use these to alter the pattern pieces before you start cutting out. They also recommend making the pattern up in woven (not printed) gingham, so that the grain of the fabric is clearly visible. However as I’ve made up Vogue patterns before, and they fitted reasonably well with a few alterations, I chose instead to cut the pattern pieces out without alterations, using my tried and trusted toile 'fabric' - frost fleece.

|

| Frost fleece - with a free thermometer! |

Frost fleece is available from garden centres or online. It is cheap; the 10 square metres pack above cost me less than £5.00. Unlike tissue paper, fleece does not tear easily, and pieces can be joined together using a sewing machine. Unlike fabric, it does not fray. I also like the fact that because it is translucent, you can clearly see the clothing underneath; so for example it is easy to tell where the waistline of a toile lies relative to your undergarments.

|

| This earlier toile shows how translucent the fleece is |

Finally, frost fleece is easy to draw on with pencil, felt tip or biro. When I designed my Eastern Influence dress I made a toile of the basic shape, then put it on the dress form and drew on the front neckline details. I then made the pattern by tracing off the pieces from the toile.

|

| Toile with extra details drawn on in pencil |

(Note: fleece is far less absorbent of ink than either fabric or paper, so while any marks made don’t rub off, a certain amount of ink transfers onto your fingers, your cutting table, and anything else the drawn-upon fleece brushes against.)

The area which I most wanted to check was the bodice length, so I marked the bust line onto the toile front pieces with red pen, and continued the line around the back. The fitting shell instructions are to make the dress up with a back opening, but I changed this to a front opening, to make it easier to get on and off.

When I tried the toile on it was easy to see that both the waist-to-bust and bust-to-shoulder sections were too long, and that I needed to shorten both. I had deliberately made the bodice up without sleeves, so that I could check if the armscye was too low. It wasn’t, so the bust-to-shoulder alteration needed to be made below the armscye.

|

| Front view of the V1004 toile with bust line and alterations clearly visible |

|

| Side view of the toile |

This discovery makes altering Vogue 2787 to fit me, ahem, 'interesting'. The front of the dress has a reverse S-shaped curve up the centre, and long curved darts which extend almost from waist to bust. So, taking out 30mm between waist and bust, and a further 20mm between bust and armscye is going to be tricky.

|

| Right front |

On the pattern piece above, the large circles with a cross in them indicate the waist and bust lines. There's not a lot of room for manoeuvre.

|

| Left front |

There is no bust marking on the left front piece, so I will have to alter it in line with the right front.

Definitely challenging!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)